Journalism. Bilingual Interview.

By Manuel Gayol Mecías…

(Left) Manuel Gayol Mecías and Dr. Aurelio de la Vega, in the Club of Critical Thinking at the Huntington Park Public Library. February 28th./ 2015.

INTERVIEW WITH MAESTRO AURELIO DE LA VEGA FOR OPEN WORD

[Translated to the English by Aurelio de la Vega]

Maestro, Doctor and Distinguished Emeritus Professor of California State University, Northridge, Aurelio de la Vega (b. La Habana, 1925) is a Cuban composer almost unknown in his motherland and, by contrast, very prominent in the international classical music scene and in particular in the United States, the country in which he resides since 1959. His dodecaphonic music-with its freely atonal, pan-tonal, and serial varieties, including electronic elements – has been exiled from Cuba, together with him, for over fifty years until, according to the Los Angeles Daily News, the prohibition of hearing and/or playing his music in the Island was supposedly lifted in 2012.

That same year the review of the Havana Archidiocesis New Word published a solid and ample article on the Cuban-American composer in which its author, Roberto Méndez, confesses that he thought that De la Vega “had died in oblivion”. It is believed that following that article, Méndez’ writing marks the rebirth of the composer in the Island’s media.

Later that same year, Cubanow.net, the official digital review of Cuban art and literature, went so far as to say that De la Vega was “an illustrious Cuban” and “one of the two most important live Cuban composers of classical music of the present”. Expressions like these would make one think that something in Cuba was truly changing. However, over two years have passed since Méndez’ article for New Word was published, and not much is known regarding how many times and in what venues De la Vega’s music has been played in Cuba, including his Prelude No. 1 for piano – a work which recently appeared on the CD Live in LA, published by Rycy Productions, and which was nominated for a Latin Grammy in 2012 as Best Work of Classical Music.

In antithesis to the official silence that up to today surrounds Aurelio de la Vega’s music, the composer has accumulated innumerable international distinctions, including the prestigious Friedheim Award of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Likewise, his music is constantly interpreted by the most important orchestras, chamber music groups, instrumentalists and singers the world over. In a parallel fashion, De la Vega has over the years offered countless lectures and seminars on contemporary music in the United States, Latin America and Europe.

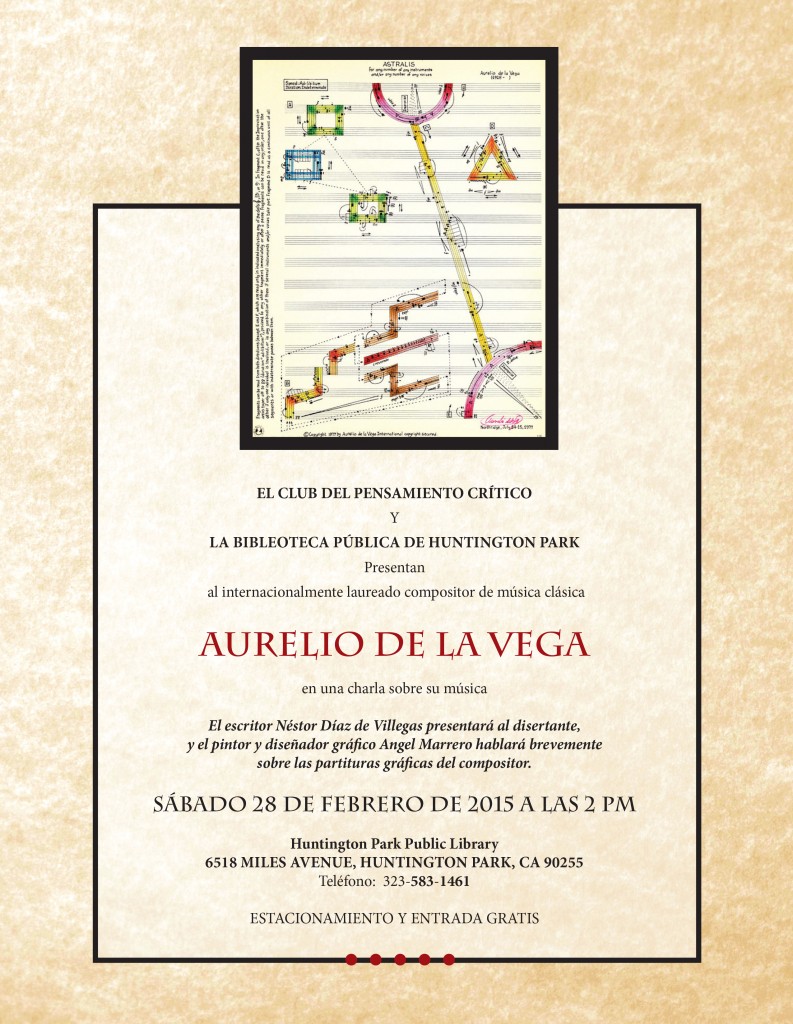

De la Vega practiced, early in his career, the several variants of dodecaphonic music, a system of composition created by Arnold Schoenberg in 1921. The composer soon became a prominent exponent of this type of music, where he brilliantly combined, with lucid intelligence, all sorts of atonal structures. One of his most important contributions was the series of graphic scores from the 1970s – the most famous of which is The Magic Labyrinth – where he combines music and painting. These hand colored graphic scores amalgamate an exquisite and beautiful visual array of pentagrams, which create innumerable forms that float on the score page, with endless amounts of single notes, melodic fragments, accidentals, dynamics, accents and reversible music cells that originate a strong array of emotions. In all of De la Vega’s compositions there is a combination of intelligence and soul that expresses the different sentimental states of the human being – a whole gamut of sounds exuding the spectrum of human universality. In a few words, this is music capable of transporting an audience to a series of high level planes of abstraction without losing track of moments of sublime serenity, intense sadness or happiness, or deep passion and grandiosity.

A remarkable aspect of Aurelio de la Vega’s personality is that he knew how to be different from all that had been done in Cuba up to the middle of the last century regarding classical music. The most extraordinary part of his rebellion is that his anti-musical nationalism was carried out without ever forgetting his Cuban roots. How to arrive, thus, at such an intrepid and mysterious symbiosis between his abstract sounds and his unabashed “Cubanness”, where he mixes his mathematical sense of structure with a sonorous overflow of the ineffable, is something difficult to explain. To eventually clarify this puzzle one must be able to unveil some key words, like intelligence, emotion, discipline, perseverance and rebelliousness.

Palabra Abierta (“Open Word”) Digital Review has today the happy possibility of penetrating more deeply into the creations of Aurelio de la Vega – one of the most important Cuban-American composers of today, and one who exhibits a profile of international relevance – by posing to him some questions that may shed light on his life and work:

1.- Manuel Gayol: Aurelio, I know you have established – from a musical – historical perspective in your magnificent essay “Nationalism and Universalism: Cuban Music in the 50s decade” – the differences between atonal, dodecaphonic and/or serial music, and traditional and even tonal classical music. However, I would like you to state briefly for our readers your explanation of such differences. Also, would you please elucidate what was the profound creative reason that moved you to embrace the type of music you compose, so distant from the easy taste of the big crowds?

Aurelio de la Vega: In the first place let us emphasize that music – the most abstract of the arts, the most difficult to understand in its most complex forms, beyond the simplistic song with text – is the last of the artistic forms of expression which appears in any culture. Just remember ancient Greece, paradigm of philosophy, theater or architecture, and one can see that in contrast to its formidable socio-cultural achievements that even today cause astonishment, music, totally monodic, stayed at a primitive, utilitarian level, without ever reaching any structural developmental form. In part, this is due to the fact that human hearing is the most elemental of the senses, very underdeveloped when you compare it to sight or smell. During the Renaissance, music, finally, flies high within Occidental culture, creating its own sonorous cosmos, free at last from the perennial ties to the word, and capable now to invent more elaborate forms liberated from utilitarian constrains. In a word, music per se, devoid of sacred, military, theatrical or funeral functions. At the beginning of the XIX century, music, in its more complex and abstract forms, starts to totally differentiate itself from popular, dance-like, text-based music, intended to be enjoyed by the masses at large. At mid XX century the schism is total. What is there in common between a Hindemith string quartet and a bolero sung by Benny Moré? Only sound. The rest is totally different: the message, the intention, the melodic-harmonic vocabulary, the structure and, aboe all, for what type of audiences were these musics composed. It seems that people do not understand that popular or commercial music is pure entertainment —from moving hips to remember simple melodies, to use the music as a vehicle for romance to listening to it as background for laughter, conversation or eating food—, while art music is an exercise for the intelligence and for the spirit.

Atonal, dodecaphonic, serial or electronic music is the result, in the XX century, of two thousand years of evolution of the thought and the creativity of human beings within the parameters of sound. The abyss between this type of music – anchored in profundity, seriousness, non-utilitarism and the enjoyment of the complex forms of sensitivity – and popular music – danceable, singable, utilitarian, superficial, amusing, simplistic – is enormous. The first type of music is not a phenomenon for the masses, and the amount of people capable of comprehending and relishing it is minimal. I can enjoy dancing, but I am moved by a Mozart symphony or by Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto. On the contrary, enormous quantities of human beings, who constantly move their behinds and sing-a-long with Celia Cruz or the Beatles, cannot grasp nor partake of a Beethoven piano concerto or of a Richard Strauss symphonic poem.

When I began to seriously compose, during my early teen years, I found that Cuban classical music (or Cuban art music, or Cuban serious music, or however you want to call it), despite the heroic efforts of Guillermo Tomás, Amadeo Roldán and Alejandro García Caturla, was stuck in a total, enervating, limited nationalism, exhuding a cultural ghetto odor. The influences came from Spain (Albéniz, Falla, the Halffters), from France (Ravel, Milhaud, Poulenc) or from neo-classicism. I found this panorama very asphyxiating, and immediately I gravitated to Central European music (Germany–Austria axis), which I considered primordial, avant-garde, fascinating and progressive. Cuban classical music of that moment, under the tutelage of Catalan composer José Ardévol and his Music Renovation Group, appeared to me skeletal, poorly developed, exhibiting big technical and structural holes. I chose to open the doors to a more ample and revolutionary music world, at that epoch represented by the Second Viennese School, with the trio Schönberg-Berg-Webern at the helm.

2.- MG: From your perspective, how was this international musical modernity which you proposed received in Cuba at that time? And, how do you evaluate your creative work not only in the Cuban context but in the international musical scene as well?

AdlV: In Cuba, in the 1940 and 1950 decades, my “internationalist” ideas were received with great distain and even with hostility. The musical powers of Ardévol and Company condemned me to an almost complete ostracism. They called me anti-Cuban, and labeled me as a dangerous foreign influence who was attempting to destroy the Spanish-Cuban musical heritage. There even appeared sarcastic articles in the press, like one by Harold Gramatges, where I was accused of being a reactionary for not embracing the Afro-Cuban culture, and, short of finding fault with me, labeled me traitor for having gone to the Schoenbergian baptismal waters to clean my cultural sins. I hope that in some future day it will be fully understood what my music-cultural crusade signified for Cuba. Curiously, even without that deserved recognition, one must point out that the post-Ardévol generation of Cuban composers digested many of my “dangerous” ideas. So we see Leo Brouwer, Carlos Fariñas, Guido López Gavilán and even Gramatges, changing bearing and adopting the post-Schoenbergian procedures: open forms, serialism, electronic elements and new musical graphology. Inside Cuba, at that moment, my music was highly revolutionary. Outside of Cuba, where my creative career has mostly occurred, my music is frequently interpreted by major orchestras, chamber music groups and soloists of great fame. The impact of my music in the international tract from 1960 to the present, is less revolutionary but no less important.

3.- MG: I know that your second devotion is painting, as you have stated several times, and it is true that the arts, and literature also, relate to music in different ways. In fact, music and painting are two ways of creation that seem to search for each other often. Such is the case of the graphic scores you created in the 1970s. Those pentagrams are most beautiful, not only as sounds but as forms as well. The delineation is geometric and full of vibrant colors, and the musical notes run through the lines and the spaces in a labyrinthic way. These scores, even when they are silent, always irradiate magic, and when they are interpreted the magic becomes more noble because they give more sense to a universal life. Within this concept of music and painting as a unit several questions come to my mind. How and why you imagined a work like The Magic Labyrinth? Did you conceive first the musical lines as an expression of your musical emotions, or your imagination created the geometric colored forms as drawings that you were relating to sounds you heard in your mind? Is there any symbolism in this symbiosis of painting and music, and if there is, what is its meaning?

AdlV: Indeed, painting is my second great cultural love. The genesis of my graphic scores from the 1970 decade is interesting. I had observed how in the musical graphology of my scores, during the 1960s, usual forms like triangles, squares, rhombs, rectangles and even circles and semi-circles were appearing. These figures were related to the entrance of instruments, orchestral clusters, dynamic aggregates and the crescendos and diminuendos. In the graphic scores from the 1970s, that are seven, I tried to combine music and painting. These colored scores can be played by one or more instruments and/or human voices, have an indeterminate duration and are, at the same time, visual works that, framed intelligently, transform themselves into real paintings to be hung on walls.

In these graphic sores the visual elements were conceived first. Inside the visual forms the sounds were inserted. These sounds are structured in diverse ways: interpretation of the fragments in three fundamental clefs (G, F and C on the third line), possible retrograde lectures, cantus firmus, dodecaphonic free elements (mainly centered in the circular or semi-circular forms), zones of ad-libitum interpretations and, always, careful realization of the melodic parameters.

The symbolism of these scores is the achievement of having broken the audio-visual limits to reincarnate, in the resulting symbiosis, in a spiritual art maybe capable of touching the Divine – as the Cuban-American painter and graphic artist Angel Marrero has stated in his magnificent essay “Different Perspectives of a Hologram” published in the 2001 program of the Concert-Homage for my 75th birthday that took place in Northridge.

4.- MG: I have listened to your music on various occasions, and I have felt like if the sounds penetrate my pores. There are arpeggios, chords, blows, noises, silences… I feel as if I am surrounded by innumerable emotional movements, which can take one to levels where many spontaneous things can be imagined. How ever, they are not images that you are imposing on me (like what happens when listening to an opera, where each theatrical moment happening on the stage has a given sonorous expression; or film music where I, invariably, have to imagine what they give me). My questions are: this musical democracy procedure where all the notes are equally important, forcing me to dream about my own dimension, is this a conscientious method in you? I mean, Aurelio, do you compose in a spontaneous way, like if in each moment of your music you would project a volley of imaginative expressions?; or do you devise a pre-conceived plan where every specific mood or gesture, every movement, every group of sounds responds to a scheme?

AdlV: The questions are not easy to answer, since the creative process is a great mystery. How does the creative mind function within the musical parameters? Is it in a conscious or sub-conscious mood one operates creatively? For example, if someone would ask me how did I conceive my String Quartet in Five Movements, In Memoriam Alban Berg, of 1957, I must say that I do not recall how the work was written. I think what happens is that one takes, digests and incorporates into one’s memory the specific technical and structural manipulations of one type of artistic creativity, in my case the musical procedures. What my imagination subsequently does is to use in a conscious way the sub-conscious practices that inform the sonic ideas. The final effectiveness of a given musical work lies in the way the elements are used. In reality it resembles the writing of a letter: one does not define the words anymore but simply uses them fluidly to structure phrases, thus communicating emotions. In my case, the work’s plan unfolds while writing, although of course there is a preconceived structural discourse: what medium is to be used, what forms are to be employed, what is the selected musical language, etc.

5.- MG: Now, at present, do you believe that the Government of the Castros really took the decision to defrost your music and stop censuring your output because its vision of the world is really changing? Is it that the supposedly “strange” sounds of your music, of a universal character, still castigate the paradoxically incomprehensible nationalism of a revolution that grew for many years under the shade of a foreign system like the Russian Soviets?

AdlV: I do not have the slightest idea of what kind of political/ cultural process permitted that my music was again heard in Cuba. I do hope that this change of attitude is sincere and permanent, and that my “strange” sounds are by now digestable and officially acceptable. I do also hope that the new winds indicate a reaffirmation of the creative liberty that, one takes heart, will reflect upon a socio-political emancipation. That would really be a great historical renaissance. And I do trust that the Cuban Government will help more, in the immediate future, the diverse groups that perform classical music in Cuba at present – groups that often enact their doings amidst great sacrifices. We know that Cuban popular music is a most lucrative business, but nations also write their biographies basing them in other forms of high culture.

6.- MG: If they would invite you officially to go to Cuba, given the new relations between the Castroite dictatorship and the Obama Government, would you go?

AdlV: I do not think so. I have a wondrous remembrance of the Cuba where I was born, where I grew up, and where I lived. She was a most beautiful lover, and I would hate to see her without teeth and with her breasts cleaning the floor. Besides, I doubt that they would receive me as they should, in a word, as the triumphant return of the prodigal son walking on a golden rug.

7.- MG: You have had several momentous moments in your musical career: prizes, homages, awards and recognitions from foreign governments for your cultural contributions. Would you mention some of the most transcendental situations of your life, instants that have meant for you an emotional episode or an acknowledgement of your life and work?

AdlV: I believe that the most memorable events of my career were: first, my appointment as Extraordinary Professor and Director of the Music Section of the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the University of Oriente, in Santiago de Cuba, in 1954, when we established for the first time in Cuba a professional music career at the university level. The first time this happened in Latin America was in Argentina (Tucumán University, decade of the 1940s), then the second time was in Cuba (University of Oriente, decade of the 1950s). Second, the premiere in London of my Elegy for string orchestra, conducted by Alberto Bolet with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, in 1954. Third, the first performances of my orchestral works Intrata (1972) and Adiós (1977), conducted by Zubin Mehta with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra. Fourth, the Friedheim Award of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (Washington, D.C., 1978). Fifth, the Concert-Homage for my 75th birthday which took place at California State University, Northridge, on April 22 of 2001, under the auspices of the Cuban-American Cultural Institute, where the Cuban-American pianist Martha Marchena played all my works for piano. Sixth, the William B. Warren Lifetime Achievement Award, bestowed upon me in 2009 by the Cintas Foundation (New York) celebrating my long musical career. Seventh, the concert in my honor that took place in the Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium (Washington, D.C., March 16, 2005) where my Version IV of The Magic Labyrinth and the Version II of Variación del Recuerdo (“Variation of the Remembrance”) were first performed. Eighth, the Concert–Homage for my 85th birthday, that took place at California State University, Northridge, on February 6, 2011 (which included almost all of my vocal works), where my wife, American soprano Anne Marie Ketchum de la Vega, magnificently interpreted Andamar-Ramadna (one of the graphic scores of the 1970s) in its Version II. And finally, in ninth place, the awarding of the Ignacio Cervantes Medal at the Cuban Cultural Center of New York in 2012.

8.- MG: I would say that you are also a very good writer, besides your inclination for painting. I have read several letters of yours and, also I keep as a special gem one of my favorite writings, your “Nationalism and Universalism. The history of Cuban classical music in the decade of 1950”. I think that article is basic an notorious within the framework of Cuban music history. Besides, I have heard you lecturing and, frankly, I discover that there is in you an intelligent and emotional discourse that never wavers, and that asserts itself in such ways as to be able to convince the audiences. This nitid coherence between reason and soul, that I have observed in you, makes me think that your music is a reflection of your own personality, strong but at the same time capable of discovering tenderness, projecting your eloquence wrapped in the kindness of a sentimental gesture. What I am going to ask you now might seem like a platitude, a mere truism, but I think your answers may clarify how a moment of creativity can be influenced by its own osmosis. Therefore, would you say that the nature of your music is a reflection of yourself, that your personality permeates your compositions, and that your music from those years in Cuba, when you fully embraced German-Austrian classical music, was an evident reflection of your rebel spirit, when you perceived the overwhelming necessity of renovating not only the cultural atmosphere in Cuba but, moreover, in the world scope?

AdlV: In reality, these are not intelligent and incisive questions but real and forceful assertions. Yes, the nature of my music is a reflection of myself; yes, my early music was heavily influenced by German-Austrian contemporary art music; yes, my music composed in Cuba during the decades of 1940 and 1950 reflected my rebellious spirit; and yes the need to renovate the Cuban and even the international cultural environment was a personal, intense desire. And…many thanks for your illustrious interest!

MG: Maestro Aurelio de la Vega, Open Word is most grateful for your most valuable answers.

♦♦♦

(Entrevista especial y original para Palabra Abierta)

El Maestro, Doctor y Profesor Emérito Distinguido de la Universidad Estatal de California en Northridge, Aurelio de la Vega (La Habana, 1925), es un compositor cubano casi desconocido en su país y, sin embargo, muy destacado en el ámbito de la música clásica internacional y en particular en la de Estados Unidos, país donde reside desde 1959. Su música dodecafónica —que puede encerrar sus variantes atonal, pan-tonal, serial y con elementos electrónicos— ha estado exiliada junto a él por 50 años (o quizás más) hasta que, según el Daily News de Los Ángeles, la prohibición de tocar y escuchar sus composiciones en Cuba supuestamente se levantó en el año 2012.

En ese mismo año la revista de la Arquidiócesis de La Habana, Palabra Nueva, publicó un rotundo y amplio artículo sobre el compositor cubanoamericano, en el que Roberto Méndez, el autor, llega a confesar que pensó que De la Vega “había muerto en el olvido”. A partir de ese artículo se cree que, muy probablemente, el trabajo de Méndez marca el renacimiento del compositor en los medios de la Isla.

Posteriormente, también en ese año, Cubanow.net, revista digital oficialista del arte y la literatura cubanos, llegó a calificar a De la Vega como “cubano ilustre” y “uno de los dos compositores cubanos vivos más importantes del momento en la llamada música culta o clásica”. Expresiones como esas harían pensar que en realidad, en Cuba, “algo estaba cambiando”. Sin embargo, han pasado ya dos años y unos meses de la publicación dePalabra Nueva y no se ha vuelto a saber detalladamente cuántas veces y en qué conciertos o funciones de música clásica en la Isla se hayan tocado sus obras, incluyendo su Preludio Nº 1 —grabado en el disco Live In LA, editado por Rycy Productions, que fue nominado para Mejor Obra de Composición Musical Clásica Contemporánea en los Premios Grammys Latinos del año 2012.

Como contraste al silencio oficial que aún hoy rodea la música de Aurelio de la Vega en su país de origen, el compositor ha recibido numerosos galardones internacionales, entre los que destaca el Friedheim Award of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Asimismo, su música ha sido interpretada por las más importantes orquestas, conjuntos de cámara, solistas instrumentales, cantantes y coros de todo el orbe. Paralelamente, ha impartido conferencias y cursos sobre música contemporánea en Estados Unidos y en numerosos países de América Latina y Europa.

De la Vega practicó desde temprano las variantes de la música dodecafónica, la cual fue fundada por Arnold Schönberg en 1921. Nuestro compositor se convirtió así en uno de los grandes exponentes de este tipo de música en la que ha sabido dominar con sobrada inteligencia las estructuras atonales, además de expresar en la escritura de sus partituras —como es el caso de su obra El laberinto mágico— un bello trazado de pentagramas, otorgándole asimismo a sus compases de sostenidos y bemoles un exquisito y fuerte conjunto de emociones. En sus composiciones hay una combinación de inteligencia y alma que expresa los diferentes estados sentimentales del ser humano —toda una gran gama de sonidos de humana universalidad. En general, puede decirse que su música es capaz de estremecer al auditorio al llevarlo a estados abstractos, incluso, de sublime serenidad, tristeza o placidez, así como a grandes momentos de pasión y grandiosidad.

Pero otra de las características de la personalidad de Aurelio de la Vega es que supo ser diferente a todo lo que se había hecho en Cuba, hasta mediados del pasado siglo, en cuanto a música clásica. Y lo más extraordinario es que quiso salirse del nacionalismo musical que siempre ha imperado en la Isla, y lo logró sin desvirtuar en ningún momento sus raíces que vienen de Cuba. Cómo llegar entonces a una fórmula tan intrépida y misteriosa, que mezcla un sentido matemático de las estructuras con un desbordamiento sonoro de lo inefable, es algo complicado de explicar. Para buscar un acercamiento a ese misterioso sentido de universalidad, yo sólo me atrevería a dar algunas palabras claves como son: inteligencia, emoción, voluntad y rebeldía.

La revista Palabra Abierta tiene hoy la feliz posibilidad de ahondar un tanto más en la obra de nuestro compositor, y ofrecer así, de primera mano, su palabra como uno de los creadores cubanoamericanos de música clásica de extraordinaria importancia mundial:

1.- Manuel Gayol: Aurelio, sé que usted ha abordado —desde una perspectiva histórico-musical en su magnífico trabajo “Nacionalismo y universalismo. La música clásica cubana en la década de los cincuenta”— la distinción entre la música atonal, dodecafónica y/o serial y la música tradicional, y hasta la clásica de registro dominante tonal. No obstante, me gustaría pedirle una breve definición de esa diferencia y que hiciera énfasis, por favor, en ¿cuál pudo ser la profunda razón creativa que le hizo decidirse por este tipo de composición, tan distanciada de los gustos facilistas de las grandes muchedumbres?

Aurelio de la Vega: En primer lugar, hagamos énfasis en que la música —la más abstracta de las artes, la más difícil de entender en sus formas de desarrollo complejo, más allá de la canción fácil con texto— es la última de las formas artísticas de expresión que aparece en cualquier cultura. A modo de recordatorio solo basta ir a la antigua Grecia, paradigma de filosofía, arquitectura o teatro, para ver que frente a sus grandes logros socioculturales que aún hoy asombran, la música, todavía monódica, se mantuvo en un nivel primitivo, utilitario y sin levantar vuelo estructural alguno. Esto se debe, entre otras cosas, al hecho de que el oído humano es el más elemental de los sentidos —poco desarrollado, por ejemplo, cuando se le compara con la vista o el olfato. A partir del Renacimiento la música, por fin, toma vuelo en la cultura occidental y, finalmente, crea su propio cosmos sonoro, despejada ya de las ataduras a la palabra y capaz de estructurar formas libres también sin sentido utilitario. O sea, música ya de por sí, sin funciones sacras, militares, teatrales o funerales. Ya a principios del siglo XIX la música, en sus formas más complejas y abstractas, comienza a diferenciarse de la música popular, bailable, con textos seculares para ser entendida por las grandes masas. En pleno siglo XX el cisma es total. ¿Qué hay de común entre un Cuarteto de Hindemith y un bolero cantado por Benny Moré? Solo el sonido. Lo demás es totalmente diferente: el mensaje, la intención, el vocabulario melódico-armónico, la estructura y, sobre todo, para qué tipo de audiencia están compuestas ambas músicas. Parece que no se entiende bien que la música popular, o comercial, es puro entretenimiento —de mover caderas a recordar melodías simples, de usar la música como vehículo para un romance a oírla como fondo para risas, conversaciones o comilonas.

La música atonal, dodecafónica, serial o puramente electrónica es el desarrollo, dentro del siglo XX, de dos milenios de evolución del pensamiento y creatividad del ser humano en su forma sonora. El abismo entre este tipo de música —que se afinca en lo profundo, en lo serio, en lo no utilitario, en el goce de formas complejas de la sensibilidad— y la música popular —bailable, cantada, utilitaria, superficial, entretenida, simple— es enorme. El primer tipo de música no es un fenómeno de masas, y el número de personas capaces de entenderla y gozarla es minúsculo. A mí puede gustarme bailar pero me conmuevo con una sinfonía de Mozart o con elConcierto para violín y orquesta de Stravinsky. Por el contrario, enormes cantidades de seres humanos, que mueven constantemente sus traseros y cantan a la par con Celia Cruz o con los Beatles, no pueden ni entender ni disfrutar un concierto de piano de Beethoven o un poema sinfónico de Richard Strauss.

Cuando yo comencé a enfrentarme con la música como compositor, durante mis años juveniles, me encontré con que la música cubana seria (o culta, o de arte, o clásica, o como quieran llamarla), pese a los grandes y nobles empeños de un Guillermo Tomás, de un Amadeo Roldán o de un Alejandro García Caturla, estaba estancada en un nacionalismo total, enervante, limitado, con olor a gueto cultural. Las influencias provenían de España (Albéniz, Falla, los Halffter), o del mundo francés (Debussy, Ravel, Milhaud, Poulenc) o del neoclasicismo. Yo encontré asfixiante ese panorama y me acerqué de inmediato a la música centroeuropea (eje Alemania-Austria) que consideré primordial, vanguardista, fascinante y progresista. La música clásica cubana de ese momento, bajo la égida del compositor catalán José Ardévol y su Grupo de Renovación Musical, me parecía esquelética, poco desarrollada, exhibiendo grandes lagunas técnicas y estructurales. Yo escogí abrir las puertas al mundo musical amplio y revolucionario, en esa época representado por la Segunda Escuela Vienesa, con el trío Schönberg-Berg-Webern a la cabeza.

2.- MG: Desde su punto de vista, ¿cómo se asumió en Cuba, en su momento, esa modernidad internacional de este tipo de música atonal o serial?; y ¿cómo ha visto usted su trabajo creativo no sólo en el contexto cubano, sino además en el ámbito mundial?

AdlV: En Cuba, en las décadas de 1940 y 1950, mis ideas “internacionalistas” fueron acogidas con gran desdén y hasta con hostilidad. Los poderes musicales de Ardévol y compañía me condenaron a un ostracismo casi total. Me tildaron de anticubano, de extranjerizante, de destructor de la herencia musical española-neoclásica. Hubo hasta artículos sarcásticos en la prensa, como uno de Harold Gramatges donde me tildaba de reaccionario por no abrazar la cultura afrocubana y haber ido hasta las aguas bautismales schönbergianas para limpiar mis pecados culturales. Algún día, espero, se comprenderá en Cuba lo que significó mi cruzada músico-cultural que, curiosamente, tuvo ecos positivos en la generación postardevoliana. Así, vemos que un Leo Brouwer, un Carlos Fariñas o el propio Gramatges cambian rumbo y adoptan los procedimientos postschönbergianos: formas abiertas, serialismo, elementos electrónicos y nueva grafología musical. Dentro de Cuba mi música fue altamente revolucionaria en su momento. Fuera de Cuba, donde se ha desarrollado mayormente mi carrera creativa, mi música es altamente respetada, interpretada de continuo por excelentes orquestas, conjuntos de cámara y solistas de gran fama. El impacto de mi música en el ámbito internacional, desde la década de 1960 hasta el presente, es menos revolucionario pero no menos importante.

3.- MG: Sé que su segunda devoción es la pintura, según usted lo ha dicho en algún momento; y es cierto también que de alguna manera las artes y la literatura misma se relacionan de diferentes modos con su música. De hecho, la música y la pintura quizás sean dos maneras de crear, muy especiales, que se buscan entre sí, como es el caso de las partituras gráficas que usted creó en la década de 1970. Esos pentagramas son hermosos, no solo como sonidos, sino como formas. El trazado es geométrico y lleno de colores vivos, y las notas musicales se pasean y corren por las líneas y espacios a modo de laberintos. Realmente esas partituras, aun cuando estén en silencio, siempre irradian algo mágico, y cuando están siendo interpretadas la magia se ennoblece más porque otorgan un mayor sentido de vida universal…

Dentro de este contexto de música y pintura se me ocurren algunas preguntas. Digamos, ¿cómo o por qué se le ocurrió una obra como El laberinto mágico?; ¿empezó a crear primero los pasajes sonoros desde la perspectiva de sus emociones musicales?; ¿o su imaginación, en primera instancia, dio paso a la creación de las figuras geométricas como dibujos y colores que usted iba escuchando y relacionando en su mente? ¿Hay algún simbolismo para usted en esta simbiosis de pintura y música, y si lo hubiera, cuál sería su significado?

AdlV: Efectivamente, la pintura es mi segundo gran amor cultural. La génesis de mis partituras gráficas de la década de los 70 es interesante. Observé cómo en la grafología musical de mi música, en la década de 1960, aparecían formas visuales tales como triángulos, cuadrados, rombos, rectángulos y hasta círculos y semicírculos, dependiendo de las entradas de los instrumentos, los clusters orquestales, los agregados dinámicos y los crescendos y diminuendos. En las partituras gráficas de los 70, que son siete, traté de combinar música y pintura. Estas partituras, en colores, pueden ser interpretadas por uno o más instrumentos y/o voces humanas, tienen una duración indeterminada y son asimismo obras visuales que, enmarcadas inteligentemente, se transforman en cuadros para ser colgados en paredes.

En estas obras gráficas lo visual fue concebido primero. Dentro de lo visual se insertaron los sonidos, que son estructurados de diversas formas: interpretación de fragmentos en tres claves fundamentales (sol, fa y do en tercera línea), posibles lecturas retrógradas, cantus firmus con selecciones interválicas dodecafónicas libres (principalmente concretados en las formas circulares o semicirculares), zonas de interpretación ad libitum y, siempre, cuidadosa realización de los parámetros melódicos.

El simbolismo de estas partituras es el logro de haber roto con los límites sonoro-visuales para reencarnar, en la simbiosis, en un arte espiritual capaz de conectarse, quizás, con lo divino —según apuntó certeramente el pintor y artista gráfico cubanoamericano Ángel Marrero en su magnífico ensayo “Different Perspectives of a Hologram”, publicado en el 2001 en el programa del Concierto Homenaje a mis 75 años realizado en Northridge.

4.- MG: Yo he escuchado su música en varias ocasiones, y he sentido como si los sonidos se colaran por mis poros. Hay arpegios, acordes, golpes, ruidos… silencios… no sé, un sinnúmero de movimientos emocionales que pueden llevarlo a uno a imaginar cosas muy espontáneas. No son imágenes que usted me esté imponiendo (como pudiera suceder con una ópera, donde cada momento en el escenario tiene su expresión sonora; o en la música de fondo de un filme, donde yo, obligadamente, tengo que imaginarme lo que me dan). Mis preguntas aquí son: esta democracia musical, en la que todas las notas son equivalentes, y que me hace a mí imaginar mi propia dimensión, ¿es consciente en usted?; quiero decir, Aurelio, ¿usted compone de una manera espontánea, como si en cada momento hiciera un solo o una descarga imaginativa?; ¿o usted se traza un plan queriendo expresar algo específico en cada movimiento, en cada grupo de sonidos?

AdlV: La pregunta se las trae, pues el proceso creativo es un gran misterio. ¿Cómo funciona la mente creativa dentro de los parámetros musicales?; ¿es consciente o subconsciente el método que se emplea? Por ejemplo, si alguien me pregunta cómo concebí mi Cuarteto en Cinco Movimientos, In Memoriam Alban Berg, de 1957, tengo que responder que no recuerdo cómo se inició la gestación de esa obra. Me parece que lo que ocurre es que uno toma, digiere e incorpora en la memoria las manipulaciones técnicas y estructurales de un modo específico de creatividad artística, en mi caso los procedimientos musicales. Lo que hace luego mi imaginación es usar conscientemente estas prácticas subconscientes que dan forma a ideas sonoras. Creo que la efectividad final de una obra dada está en cómo esos elementos fueron usados. En cierto modo es como escribir una carta: ya uno no define las palabras si no que las usa fluidamente para estructurar frases y así comunicar emociones. En mi caso, el plan de una obra se va desarrollando en la escritura, aunque claro existe un preconcebido discurso estructural: qué medio se va a usar, qué formas van a decidirse, qué lenguaje es el escogido, etc.

5.- MG: ¿Ahora, en la actualidad, cree usted que el Gobierno de los Castro en verdad tomó la decisión de descongelar su música, de quitarle la censura a sus obras, porque realmente está cambiando su visión del mundo? ¿Es que los supuestos “extraños” sonidos de su música, de carácter universal, fustigaron (y fustigan aún) el incomprensible por paradójico nacionalismo de una revolución que se arropó por largos años dentro de un sistema extranjero como el soviético, centrado por Rusia?

AdlV: No tengo la menor idea de cuál fue el proceso político-cultural que permitió que en Cuba se escuchase de nuevo mi música. Espero que este cambio de actitud sea sincero y permanente, y que mis “extraños” sonidos sean ya digeribles y oficialmente aceptables a estas alturas. Espero, asimismo, que los nuevos vientos indiquen una reafirmación de la libertad creativa, la cual, de algún modo, pueda pronto reflejarse en una libertad sociopolítica. Eso sería un gran y verdadero renacimiento histórico. Y espero que el Gobierno cubano apoye más en el futuro a los diversos grupos que actualmente hacen música clásica en Cuba, los cuales realizan sus funciones con grandes sacrificios. Ya sabemos que el cultivo de la música popular cubana es un gran negocio muy lucrativo, pero las naciones escriben también sus biografías basadas estas en otras formas de alta cultura.

6.- MG: Si le invitaran oficialmente a ir a Cuba, con estas nuevas relaciones que se están gestando entre la dictadura castrista y el Gobierno de Obama, ¿usted iría?

AdlV: No creo. Yo tengo un recuerdo maravilloso de la Cuba en que nací, crecí y habité. Fue una amante hermosísima, y me dolería volverla a ver sin dientes y con los senos limpiando el piso. Además, dudo que me recibirían como deberían hacerlo, o sea, como el retorno triunfante del hijo pródigo caminando sobre alfombra dorada.

7.- MG: Ha tenido usted unos cuantos momentos cumbres en su carrera: premios, menciones, homenajes. Yo le pregunto: ¿podría hablarme de algunas de las situaciones más trascendentales de su existencia; momentos que hayan significado para usted —de manera especial— una gran emoción o reconocimiento por su vida y obra?

AdlV: Creo que los momentos musicales más emocionantes de mi carrera fueron: primero, mi nombramiento como Profesor Extraordinario y Director de la Sección de Música de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Oriente, en Santiago de Cuba, en 1954, cuando fundamos, por vez primera en Cuba, una carrera musical a nivel universitario. La primera ocasión en que esto ocurrió en América Latina fue en la Argentina (Universidad de Tucumán, en la década de los 40), la segunda fue en Cuba (Universidad de Oriente, década de los 50). En segundo lugar está el estreno en Londres de mi Elegía para orquesta de cuerdas, con la Royal Philharmonic Orchestra dirigida por Alberto Bolet, en 1954. En tercer lugar, los estrenos de mis obras orquestales Intrata (1972) y Adiós (1977), dirigidas por Zubin Mehta con la Orquesta Filarmónica de Los Ángeles. En cuarto lugar, el Premio Friedheim del Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (Washington, DC, 1978). En quinto lugar, el concierto en homenaje por mis 75 años realizado en la Universidad Estatal de California en Northridge, bajo el patrocinio del Instituto Cultural Cubano-Americano, en abril 22 del 2001, donde la pianista cubanoestadounidense Martha Marchena interpretó todas mis obras para piano. En sexto lugar, el Premio William B. Warren Lifetime Achievement Award, otorgado en el 2009 por la Fundación Cintas de Nueva York en celebración de mi larga carrera musical. En séptimo lugar, el concierto en mi honor celebrado en el Coolidge Auditorium, de la Biblioteca del Congreso Norteamericano (Washington, DC, marzo 16, 2005), donde se estrenaron la Versión IV del Laberinto mágico y la Versión II de Variación del Recuerdo. En octavo lugar, el concierto también en homenaje por mi octogésimo quinto aniversario, celebrado en la Universidad Estatal de California en Northridge, en febrero 6 del 2011 (dedicado a la casi totalidad de mi obra vocal), donde mi esposa, la soprano norteamericana Anne Marie Ketchum de la Vega interpretó inolvidablemente Andamar-Ramadna(una de las partituras gráficas de la década de 1970) en su Versión II. Y finalmente, en noveno lugar, el otorgamiento de la Medalla Ignacio Cervantes, ceremonia que tuvo lugar en el Centro Cultural Cubano de Nueva York en el año 2012.

8.- MG: Yo diría que en usted también —además de su inclinación por la pintura— hay un buen y culto escritor. He leído cartas suyas, y leí asimismo, y he separado como uno de mis escritos preferidos, su “Nacionalismo y universalismo. La historia de la música clásica cubana en la década de los cincuenta”. Pienso que ese artículo es notorio dentro de la historia de la música cubana. Además, le he escuchado disertar en público, y francamente descubro que en usted hay un discurso de inteligencia y emoción que nunca pierde el hilo, que se conjuga de una manera exacta para lograr una persuasión en el lector. Esa coherencia nítida que he advertido en usted, entre raciocinio y alma, me dice entonces que su música es un reflejo de su propia personalidad: fuerte pero que al mismo tiempo sabe discurrir con la ternura, sabe ubicar su voz, sabe proyectar su elocuencia en la precisa caricia de un gesto. Esto que voy a preguntarle ahora podría parecer entonces una perogrullada, pero creo que en realidad sus respuestas ayudarían para un acercamiento al sentido de la creatividad y su ósmosis, de cómo puede darse un momento de creatividad y de dónde puede ser influido. En fin, ¿estaría usted conforme en decir que la naturaleza de su música es espontáneamente usted mismo; que su personalidad es unísona con sus composiciones, y que de alguna manera su música, de aquellos primeros tiempos en Cuba, que estuvo estimulada por la música clásica alemana, fue un vivo reflejo de su espíritu de rebeldía; que usted percibió la necesidad de aires de renovación no sólo en la Isla, sino además en el ámbito mundial?

AdlV: En realidad podría decirse que estas no son solo preguntas incisivas e inteligentes si no que son afirmaciones reales y contundentes. Sí, la naturaleza de mi música soy yo mismo; sí, mi música temprana fue estimulada por la música clásica alemana-austriaca; sí, mi música compuesta en Cuba durante las décadas de 1940 y 1950 reflejó mi espíritu de rebeldía, y sí, para mí la renovación de los aires culturales cubanos e internacionales fue un deseo personal muy intenso e importante. Y ¡muchas gracias por su esclarecido interés!

MG: Maestro Aurelio de la Vega, Palabra Abierta le está muy agradecida por sus valiosas respuestas.

[Esta entrevista especial con Aurelio de la Vega es original de Palabra Abierta, dada el 10 de julio de 2015]

©Palabra Abierta y Manuel Gayol